Some Final Thoughts

Sometimes one is ready to return home at the end of a journey, and sometimes one is not. It was the latter for me on this trip, as indicated by my mood boarding the plane in Dubai to return to the U.S. In spite of having thrown myself enthusiastically into both pleasant situations and uncomfortable detours, a part of me felt like I’d missed out on some opportunity that I couldn’t identify or describe. The journey’s end came before its ending.

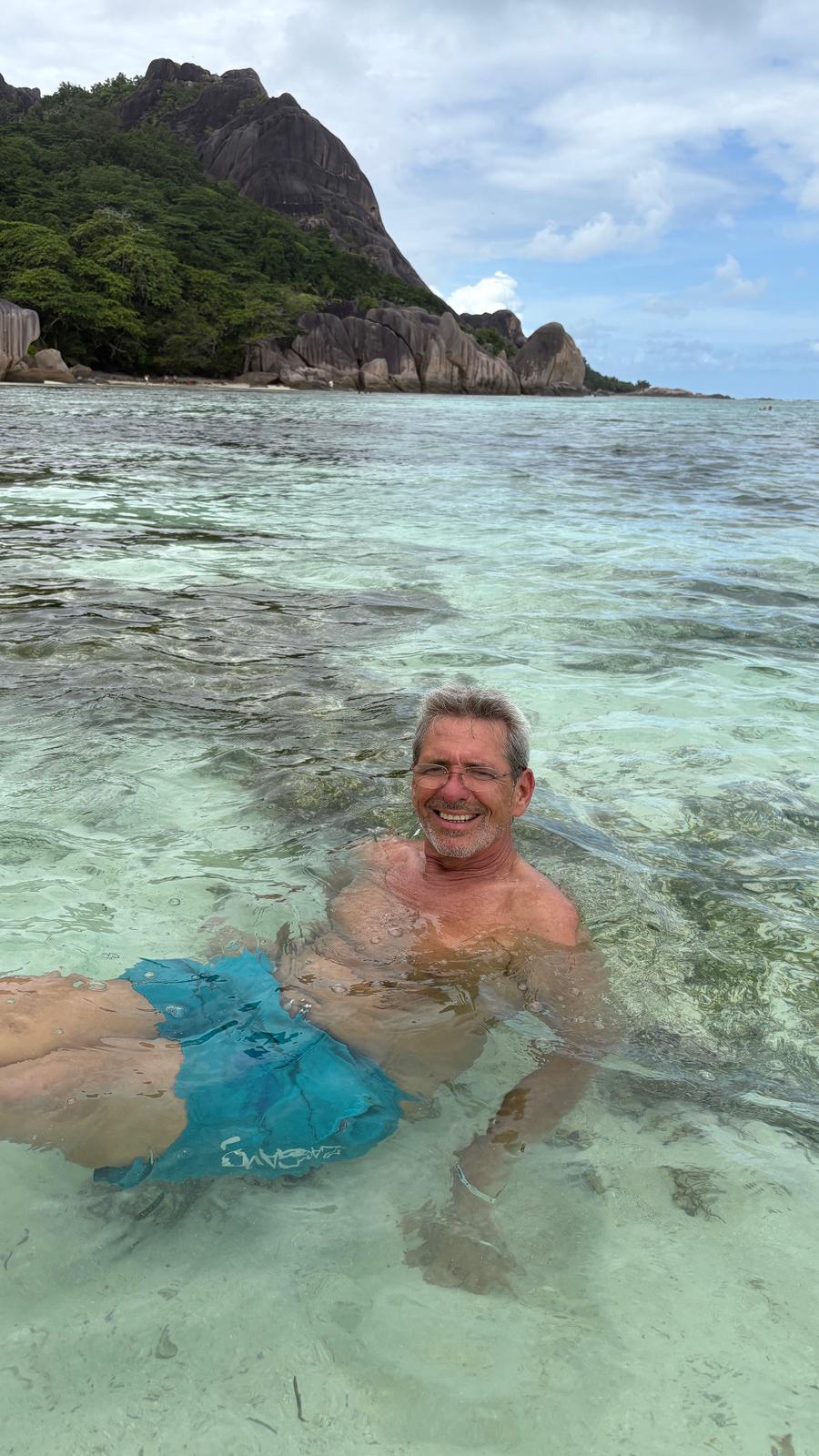

Which is not to say that I regret traveling almost exactly halfway around the world. If money and time permitted, I’d pack my bag and be out the door again tomorrow. There were many brilliant moments sailing in the Seychelles, and even (especially?) in the trials and tribulations of getting there and back. But one of the ways of looking at a piece of art is to analyze what it leaves out, so if a journey is a manifestation of the art of traveling, then perhaps it is useful to describe what the journey was not.

Touch and Go

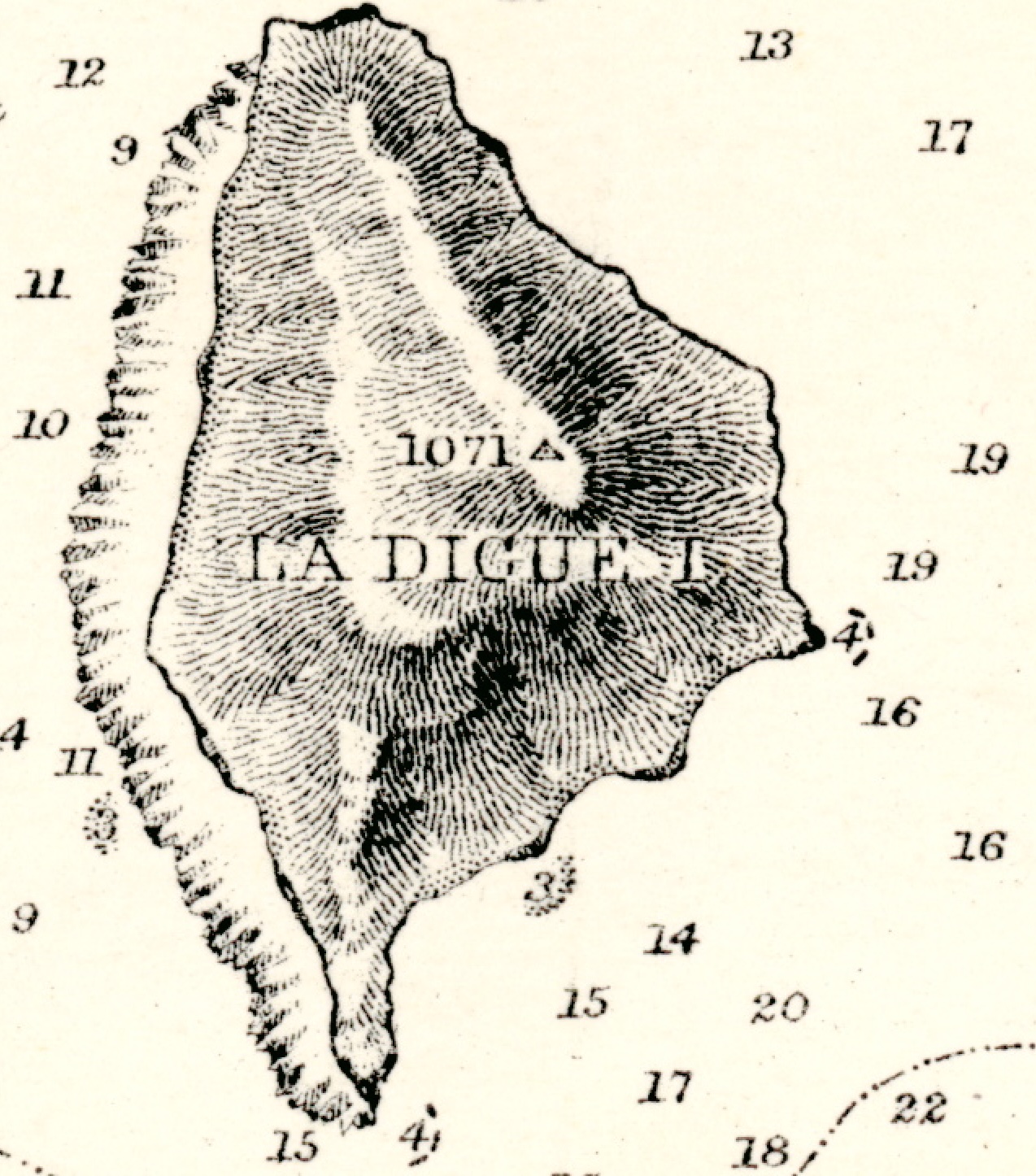

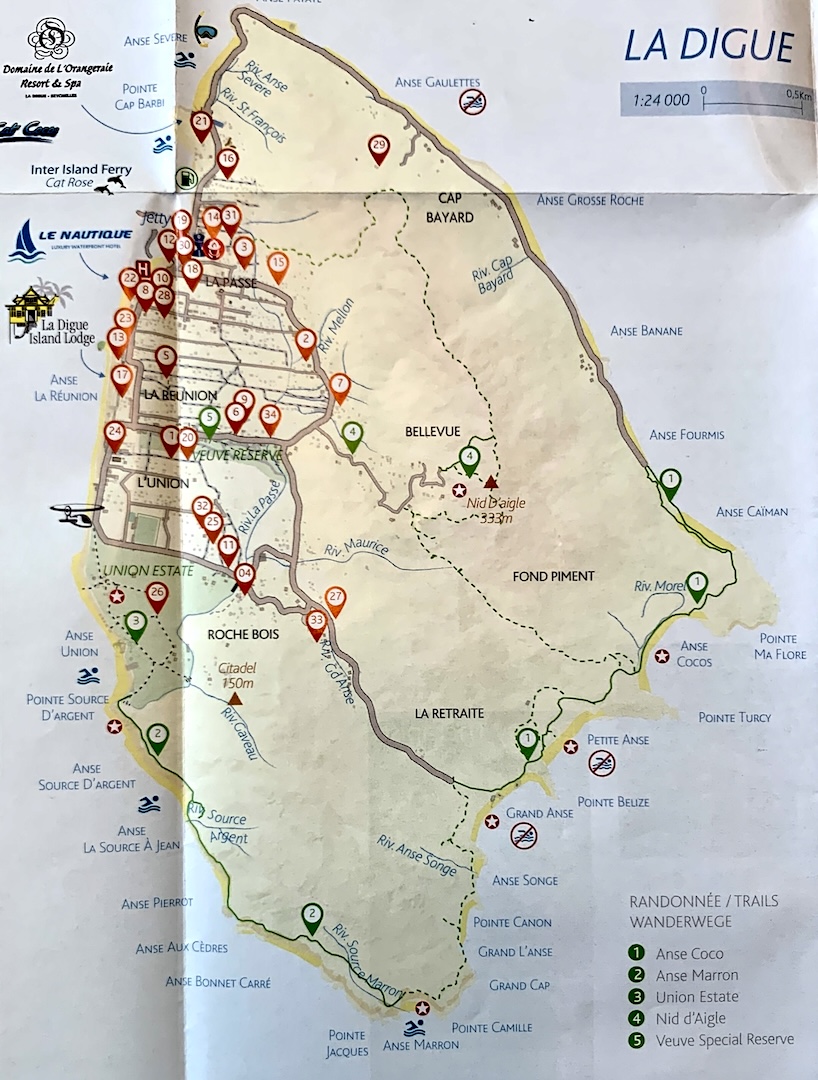

I often find it difficult when I’m walking or driving to stop and turn around because of an almost irresistible urge to “see what’s around the next bend.” Being on a boat with access to numerous tropical islands induces a similar impulse, especially when the time on board is limited. No matter how beautiful or peaceful the current anchorage is, there’s a thrill in seeing what’s around the next point, the next cove, the next harbor, the next island. It’s the dopamine rush of putting another mark on the map, as evidenced by the many red pins appearing in my prior blog posts.

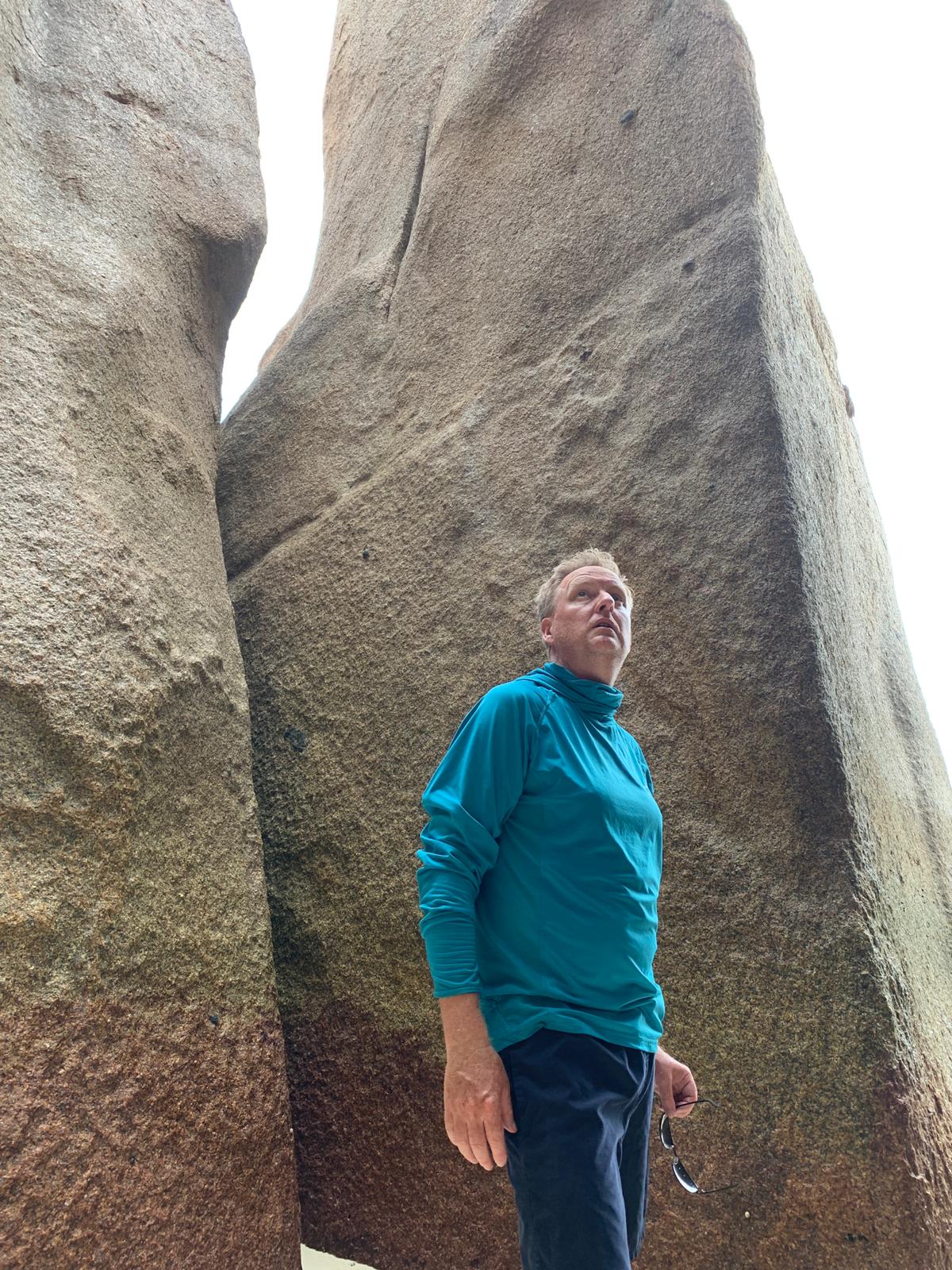

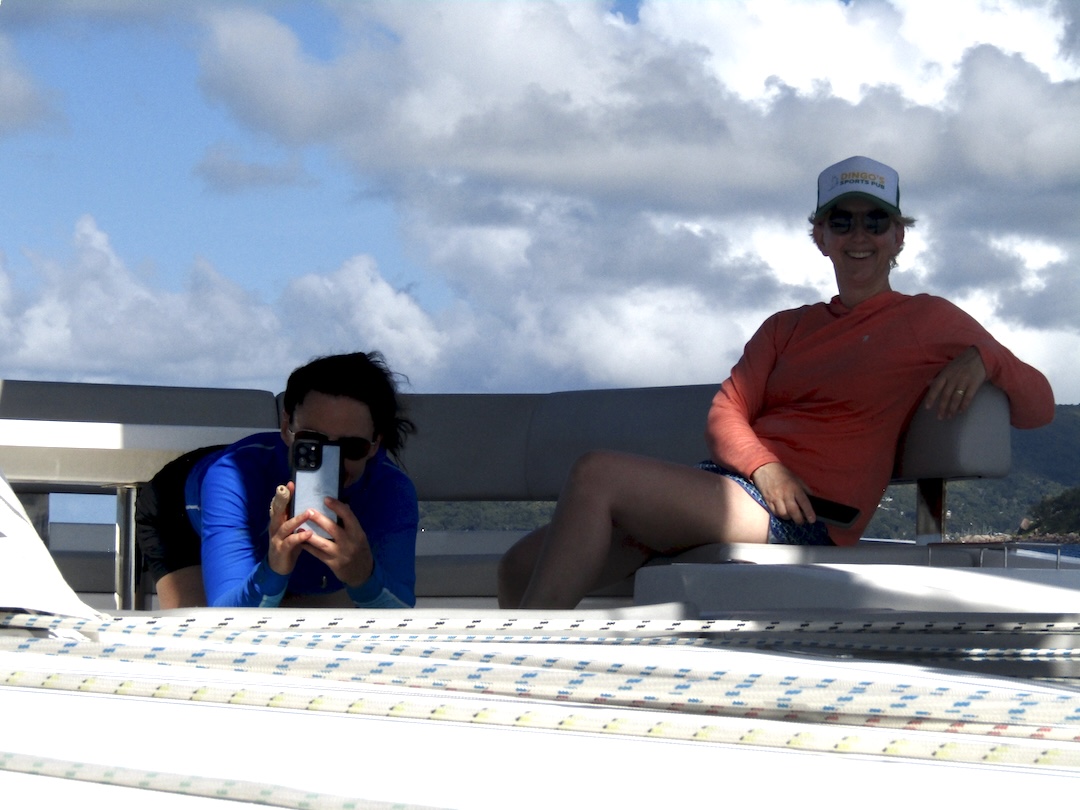

The cost of that restlessness is missing the chance to commune with a place. It was that lack of connection that I think led to the frustratingly few interesting photographs that I took during the trip. The deck of a boat doesn’t offer as many photo opportunities as one might think. Pictures of islands, beaches, palm trees and sunsets quickly become indistinguishable. When I was able to spend some time on shore, the energy required to be observant was quickly depleted by the heat and humidity. The most important piece of photography equipment is a good pair of shoes, and the pictures I was most pleased with were taken while I was on foot. I wish I’d spent more time walking, especially on Praslin Island, which seemed like it might have been the most quintessentially Seychellois.

The Seychellois Cure

Besides better photo opportunities, walking also removes you from the air-conditioned culture bubble that seems to define modern vacationing. It increases the likelihood of interacting with the locals on their terms instead of yours. Since I didn’t do as much walking as I would have liked, interactions with the Seychellois that I would consider authentic were limited, and therefore my perception of the local culture might be totally off the mark, but I offer the following observation anyway.

The Seychelles felt like a beautiful hospital that the rest of the world visits in order to convalesce and recover from the ailments and diseases that their cultures back home suffer from. Everything on the islands was unbelievably tidy. There was no litter to speak of, and on many occasions we saw people going so far as to sweep up the ceaseless detritus of the jungle, stacking it in neat piles mostly hidden from view. With only modest means, they couldn’t keep up with putting a fresh coat of paint on everything that needed it, but when the paint had blistered and cracked from the inexorable effects of the tropical humidity, the walls were always scraped smooth and clean.

The locals I met were all kind, friendly and helpful, yet there was something very practical and no-nonsense about them. They had the demeanor of a capable nurse or physical therapist: there to help, but the efficacy of the cure depended largely on the patients’ own attitudes and behaviors (and adjustments thereof). Human nature being what it is, I’m sure there are internal problems and strife that an outsider like me wouldn’t be privy to. As a small nation, they struggle to protect themselves from powerful external forces looking to use their country for drug running, money laundering, and the exploitation of natural resources. They are keenly aware of how dependent they are on money from tourism. In spite of all that, there was a groundedness and determination stemming from a local wisdom that I wish I’d had more exposure to.

Discontent and Despair

Touching down again at Newark Liberty International Airport did not feel good, at all. Almost every aspect of the place – the noise, the disorganization, the bad design, the carelessness, the terrible food – made me chagrined at being an American. I had written the phrase “ailments and diseases” in my notes before ever leaving the Seychelles, so I’d had a suspicion some culture shock might be waiting for me when I got back, I just didn’t realize how sensitive to it I would be. I postponed writing this final blog post for a few weeks while I tried to identify the sickness I felt being back in the U.S., and more importantly, its causes. Then I found this quote:

There is much sadness in our societies even though they are full of wealth. We are an overfed people with societies choked by the amount of garbage we create. We infest everything, we buy things we don’t need and then we live in despair paying bills.

~ José Mujica, former President of Uruguay (source)

While I would have preferred to arrive at such an astute diagnosis myself, it relieved me of the burden of finding my own words to make sense of the final leg of my journey. I don’t share Señor Mujica’s opinion that some political system will lead us out of the sadness and despair, but he is not wrong that people of the “developed” world are trapped by their own insatiable appetites and slaves to their own dissatisfaction.

It is of course brutally ironic that I paid thousands of dollars for the privilege of sitting on airplanes traveling nearly 600 miles per hour for 22 hours in order to get far enough away to see the effects of the discontent, and then spend another 22 hours coming back only to be infected by it again. Now that I’ve written it down, perhaps the Seychellois Cure has started to take effect: tidy up the little speck of creation that has been put in my care; be adaptable and patient whether I’m ten thousand miles or ten feet from home; be content with what is, and grateful for what isn’t.